|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Misa de Diálogo - CXXVII

Autoridad reemplazada por 'Servicio'

Guardini: 'Su autoridad es la autoridad del servicio'

“Esta autoridad no es de dominación, por lo que el individuo está sujeto a ella, pero la Iglesia es la gran servidora de los individuos, y por este servicio se convierte en lo que realmente es. Su autoridad es la autoridad del servicio”. (1)

Guardini fue uno de los primeros teólogos del siglo XX en retomar y desarrollar la idea de la autoridad clerical como un “servicio” amorfo y generalizado en el que el sacerdote ordenado ya no es visto como un mediador de autoridad de Dios, sino como siervo del pueblo. La implicación de sus palabras citadas anteriormente es que los fieles no están sujetos a la autoridad de la Iglesia investida en la Jerarquía, sino solo directamente a Dios y a su propia conciencia, una posición luterana clásica. Esto explica por qué Guardini consideraba el ejercicio del poder clerical, especialmente cuando exige la obediencia de sus súbditos, vinculando bajo pena de pecado, como una forma de “dominación” (en sentido peyorativo).

En cuanto al tema del papado como monarquía, Guardini dio a conocer su opinión de la siguiente manera indirecta:

“En el Concilio, cuando el Papa Pablo VI dejó la Tiara con su triple corona sobre el altar para que pudiera venderse y su precio pudiera usarse para alimentar a los hambrientos, quiso que este acto fuera un símbolo y una lección múltiple”. (2)

Pablo VI aparta la tiara papal, signo de su rechazo a la estructura monárquica de la Iglesia

De hecho, el término Cristo Rey no se menciona ni una sola vez en ninguno de los documentos del Vaticano II, a pesar de que el Papa Pío XI, a principios del mismo siglo, había instituido una Fiesta para celebrar el Reinado de Cristo. El abandono de la Tiara en el contexto de alimentar a los pobres da un mensaje claro de que el objetivo enteramente sobrenatural del papado ha sido degradado y disminuído para dar paso a consideraciones puramente naturalistas, humanitarias y seculares.

‘Nosotros no nos enseñoreamos de vuestra fe, servimos a vuestro gozo’

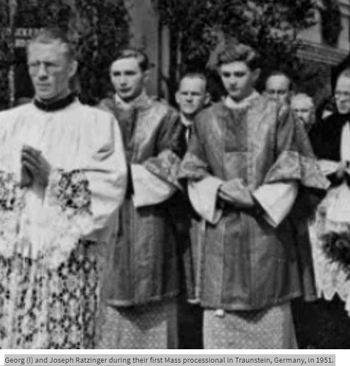

Para cualquiera que esté familiarizado con la retórica posterior al Vaticano II, este subtítulo puede sonar como si hubiera sido escrito por el Papa Francisco. Pero fue, de hecho, el lema que Benedicto XVI, recordando su larga carrera eclesiástica, dijo que había elegido imprimir en las tarjetas de invitación a la primera Misa que celebró después de su ordenación sacerdotal en 1951.

Ratzinger, cuarto por la izquierda, en su primera Misa, ya afirma que tiene otra visión de la autoridad

La noción de sustituir gobernar por servir ha sido durante mucho tiempo el leitmotiv de la mayoría de los pensadores progresistas que intentaron subvertir la Constitución de la Iglesia, comenzando con los primeros modernistas como George Tyrrell y jugadores clave en el Movimiento Litúrgico como Romano Guardini.

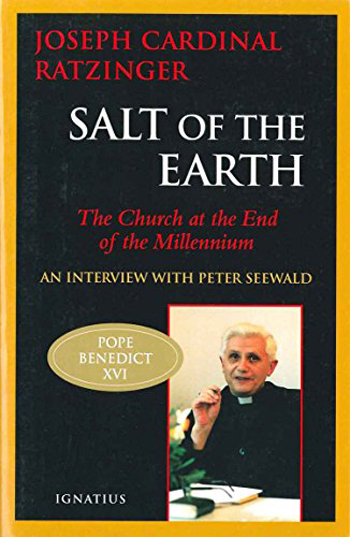

En su autobiografía por entrevista con el periodista Peter Seewald, el Papa Benedicto explicó que su lema juvenil era “parte de una comprensión contemporánea del sacerdocio”. (3) Pero el lema no representa la ortodoxia teológica que prevaleció a mediados de la década de 1950. Por el contrario, antes del Concilio Vaticano II habría sido ininteligible para todos menos para un cierto grupo de teólogos rebeldes –una vanguardia revolucionaria– que finalmente lograron cambiar la forma en que la Iglesia moderna considera el sacerdocio.

Incluso en sus últimos años, el Papa Benedicto XVI aún se aferraba a la opinión de rigueur entre los progresistas de que la enseñanza tradicional de la Iglesia sobre el munus regendi era una forma de “clericalismo”:

“No solo éramos conscientes de que el clericalismo está mal y el sacerdote es siempre un servidor, sino que también hicimos un gran esfuerzo interior para no ponernos en un pedestal alto”. (4)

Incluso si esta declaración no pretende ser un ejemplo de señalización de virtud, conlleva la desagradable implicación de que los sacerdotes modernos son superiores a sus antepasados en la virtud de la humildad. La suposición básica de que los sacerdotes se han puesto en un alto pedestal es una calumnia contra el sacerdocio; no reconoce que los sacerdotes han sido llamados y ordenados a un destino superior como mediadores entre Dios y el hombre para la salvación de las almas.

Todavía recordando la formación progresista que recibió en sus días de seminario, que lo indujo a ver el sacerdocio ordenado como algo que no debía ser admirado, el Papa Benedicto XVI afirmó:

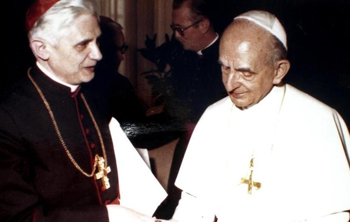

Pablo VI, Benedicto XVI y Francisco - todos compartían la misma visión progresista de la autoridad

Esta declaración parece deberse más al prejuicio ideológico contra el estatus superior del sacerdocio que siempre había sido motivo de discordia entre los progresistas. Está en línea con el pensamiento del P. Tyrrell quien, como hemos visto, se describió a sí mismo como "demasiado democrático incluso para disfrutar de la 'superioridad' de la dignidad sacerdotal". (6)

Lamentablemente, los herederos modernos de Tyrrell, que también rechazan la dicotomía superior-inferior, derriban lo que la Iglesia ha enseñado con la mayor certeza y exactitud: que el hombre está sujeto a la soberanía de Dios, que es la meta de toda la creación, y que los fieles están subordinados a la Jerarquía que representa a Cristo, Cabeza de la Iglesia.

Además, una característica clave de los revolucionarios anteriores al Vaticano II es que sus ideas no se inspiraron en la tradición católica sino en sus propias opiniones personales. Benedicto XVI, por ejemplo, admitió que el lema impreso en su tarjeta de invitación expresando su visión del sacerdocio (servir y no gobernar) estaba inspirado en su propia interpretación privada de la Biblia:

“Entonces, la declaración en la invitación expresó una motivación central para mí. Este fue un motivo que encontré en varios textos en las lecciones y lecturas de la Sagrada Escritura, y que expresaba algo muy importante para mí”. (7)

Si bien hay numerosas referencias en las Escrituras a la necesidad de la humildad entre los gobernantes, no hay nada que sustituya "servicio" por "gobierno", como parece implicar el lema. Aquí Benedicto XVI reveló sin darse cuenta el carácter infundado de la acusación de “clericalismo” lanzada contra la Jerarquía tradicional.

Pero si los fundamentos de la acusación no se pueden encontrar ni en las Escrituras ni en la Tradición, debemos concluir que la burla del “clericalismo” es simplemente una construcción artificial, una invención de los progresistas. De lo contrario, ¿por qué el concepto de gobernar sobre los fieles se ha convertido en un tema tan neurálgico en la Iglesia desde el Concilio Vaticano II? Incluso los Papas son reacios a mencionarlo e insisten en redefinirlo bajo los títulos desarmadores de "servicio", "don" y "amor".

“Cuando el sacerdocio, el episcopado y el papado se entienden en términos de gobierno, las cosas están mal”

“La categoría que corresponde al sacerdocio no es la de regla… Cuando el sacerdocio, el episcopado y el papado se entienden esencialmente en términos de regla, entonces las cosas están esencialmente equivocadas y distorsionadas”. (8)

Aquí Ratzinger se mostró como un maestro del oscuro arte de la ofuscación y el doble discurso. Se podría inferir fácilmente de estas palabras que gobernar no pertenece a la esencia del sacerdocio. Pero esto entra en conflicto con la enseñanza ortodoxa de que el munus regendi es uno de los poderes sagrados conferidos al sacerdote en su ordenación: El sacerdote es un gobernante en el sentido sobrenatural.

Lo que sea que quiso decir no está exactamente claro. Todo lo que sabemos es que su idea no provino directamente de la tradición católica, ya que describió la nueva enseñanza (que, significativamente, ningún católico tradicional había pedido) como “una forma importante y diferente de ver las cosas”. (9)

Siendo uno de los teólogos progresistas de su época, Ratzinger se sentía incómodo con la idea de una Jerarquía con derecho a gobernar, en el sentido de ejercer poder o autoridad soberana sobre otros miembros de la Iglesia. Así, construyó un relato plausible del origen griego de la palabra jerarquía con la evidente intención de desviar la atención de los fieles de su verdadero significado tal como se entiende en la Tradición.

Jerarquía: del griego hieros (sagrado) y archon (gobernante o señor) (10) siempre se entendió en la Iglesia como el gobierno de los gobernantes eclesiásticos que habían recibido sus poderes sacerdotales. a través de la Ordenación. Pero este concepto era demasiado desagradable para los progresistas que querían demoler la estructura monárquica de la Iglesia y reemplazarla con un modelo democrático basado únicamente en el bautismo. Entonces, Ratzinger hizo un juego de manos al señalar una ambigüedad en la palabra griega archē, (11) que puede significar tanto origen como regla, y eligió el primer significado sobre el segundo como la traducción correcta. (12)

Este acto de desvío proporcionó una excusa lista para que los progresistas se deshicieran de la interpretación tradicional de jerarquía, mientras que hacía prácticamente imposible que cualquier persona sin conocimiento de la etimología griega juzgara la confiabilidad de su traducción.

El Papa del pueblo, un nuevo concepto de papado

En síntesis, su posición teológica sobre la Jerarquía, fiel al Concilio Vaticano II, no fue diferente a la del P. Tyrrell y todos los progresistas de persuasión neomodernista. Se puede resumir en su declaración:

“La forma de gobernar de Jesús no era a través del dominio, sino en el humilde y amoroso servicio del lavatorio de los pies”. (14)

Todos los ingredientes de la perspectiva anticlerical modernista están contenidos allí: los clérigos deben servir al pueblo en lugar de gobernar sobre él: el mensaje encapsulado en el lema de Ratzinger.

Después del discurso de apertura del Papa Juan XXIII en el Concilio, en el que recomendó la “medicina de la misericordia”, se concibió un nuevo enfoque para gobernar la Iglesia. Estaría libre de prácticas “inquisitoriales” como la caza de herejías, la censura y las leyes punitivas, con menos énfasis en la imposición de penitencias, ayunos y abstinencias, mandatos y sanciones, y mucho más en la libertad del individuo.

Si Benedicto todavía hablaba de gobernar la Iglesia, era sólo en el sentido de “guiar”, “instruir”, “inspirar” y “sostener” al “Pueblo de Dios”; (15) en otras palabras, con estructuras de autoridad emasculadas compatibles con la “Nueva Evangelización” del Vaticano II.

Continuará ...

- Romano Guardini, The Church of the Lord: On the Nature and Mission of the Church, Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1966, p. 105.

- Ibid., p. 107.

- Benedict XVI, Peter Seewald, Last Testament: In His Own Words, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016, p. 87.

- Ibid., p. 87.

- Ibid., p. 88.

- G. Tyrrell, ‘To Wilfrid Ward Esq.’, April 8, 1906, apud Maude Petrie (ed.), George Tyrrell’s Letters, London: T. Fisher Unwin Ltd., 1920, p. 102.

- Benedict XVI, Peter Seewald, op. cit., p. 88.

- Joseph Ratzinger, Salt of the Earth: Christianity and the Catholic Church at the End of the Millennium, An Interview with Peter Seewald, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1997, p. 191.

- Ibid.

- The archon (ἄρχων) was the title of the chief magistrates in ancient Greek states.

- Archē (αρχη) originally had the meaning of something that was in the beginning, designating the source, origin or root of things that exist. By extension, it came to mean power, sovereignty and domination derived from a first principle.

- Ratzinger, ibid., p. 190.

- Ratzinger concentrated solely on the “sacred origin” aspect of the word hierarchy, and omitted its meaning of “sacred rule.” He clouded the issue in circumlocution, stating that the power of the sacred origin is “the ever-new beginning of every generation in the Church.” This gives the impression of a return to the sources to re-apply the original principles to each new generation to suit the outlook of contemporary man. But this digression is not an argument ad rem. It does nothing to prove that the traditional concept of the hierarchy is “essentially wrong and distorted.”

- Benedict, ‘Authority and hierarchy in the Church: Service lived in pure giving’, Address given in St Peter’s Square, May 26, 2010

- This approach features very clearly in his above-mentioned May 2010 speech.

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |